A SEQUENCE OF EVENTS IN THE LIVES OF THE DORMANT

Jumana Emil Abboud, Mohamed Abdelkarim, Black Quantum Futurism, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh & Rozenn Quéré, Haytham El-Wardany, Katia Kameli, Karrabing Film Collective, Kristiina Koskentola, Melissa E. Logan, Danie Meyer, Denzel Russell, Julius Vapiano

17 October 2020 - 23 May 2021

Opening: Fri 16 October, 4 — 11 p.m.

“Can you say dormant to reference water? Life? Spirit, jinn, words?

Words that speak like magic cure or poison - to bewitch into sleep-fulness or numbness

Words that speak like chanting mumbling cures to awaken. Just like a kiss from the deep

Dark a hundred years after”

Jumana Emil Abboud

This exhibition looks at different types of narratives as emancipatory tools to reclaim community and land that have been ravaged by settler colonialism, imperialism and neoliberal hegemonies. What persist are the stories, long after territories are infringed upon or people displaced. They survive, even if only in fragments or as bleak memories, leaving a record which resurrects a desire to bring back the community and the place it inhabited. When put back together into narrative structures, these remnants of stories, very often referring to traumatic collective and individual experiences, have the potential to give new impulses to political struggles. The difference between the real or historical and the fictional loses any importance here, instead what counts is the futurist potential of the story – its capacity to reimagine and influence the past and the future.

In an interview by Salman Rushdie with Edward Said, Said speaks about the unmaking of the hegemonic institutionalized narratives through the repeated telling of stories by the underdog. He says: “There seems to be nothing in the world that sustains the story, unless you’re telling it, it’s going to drop and disappear; it needs to be perpetually told and retold, whereas the other narrative is there and is institutionalized”.[1] When the land is lost, the story remains, but it only survives by its repeated telling, and this repeated collective telling lives through the story, commemorating the loss and the life. The conception that indigenous people are in harmony with nature and can live off the land is essentialist and romantic. Actually the knowledge, which a community possesses, comes from its practice, and this practice requires an access to the ancestral knowledge and to the land, both stripped by the colonial powers.

A good example of this are folktales. They are educational tools to pass knowledge from one generation to the next, where the narrative is in opposition or parallel to the prevailing class narrative. Folktales contain many layers and maintain the “social characteristics of the people involved”, and they can be widely and easily spread.[2] In addition, the fact that the tales are without an author allows an expression of political views which would be punishable if said by an individual. The knowledge embedded in the folktales travels and changes as it is told and retold by different communities and in different times. The historicized folktale[3] can be seen as the literary production of a collective, drawing from the material conditions of a particular community. The stories are often related to a particular location, and among many functions, they protect this location’s natural sources and nurture them. The cultural is intertwined here with the economic, and different cultural identities intersect by means of similar economic realities. Yet the territory cannot be reclaimed unless the community embodies the stories. A story does not live without its community: the community produces the story and the story produces the community.

It is clear that the attempt to reclaim through narrativity requires the bending and breaking of the traditional concept of time: the retelling of the story always happens in a particular time and is reshaped by its current conditions. In this way a story is always “stretched” in time – the past that it refers to becomes “a space of open possibility, speculation, and active revision by multiple generations of people situated in the relative future”.[4] In other words: if you own the past, rejecting the oppressive linear concept of time, you can take hold of the future.

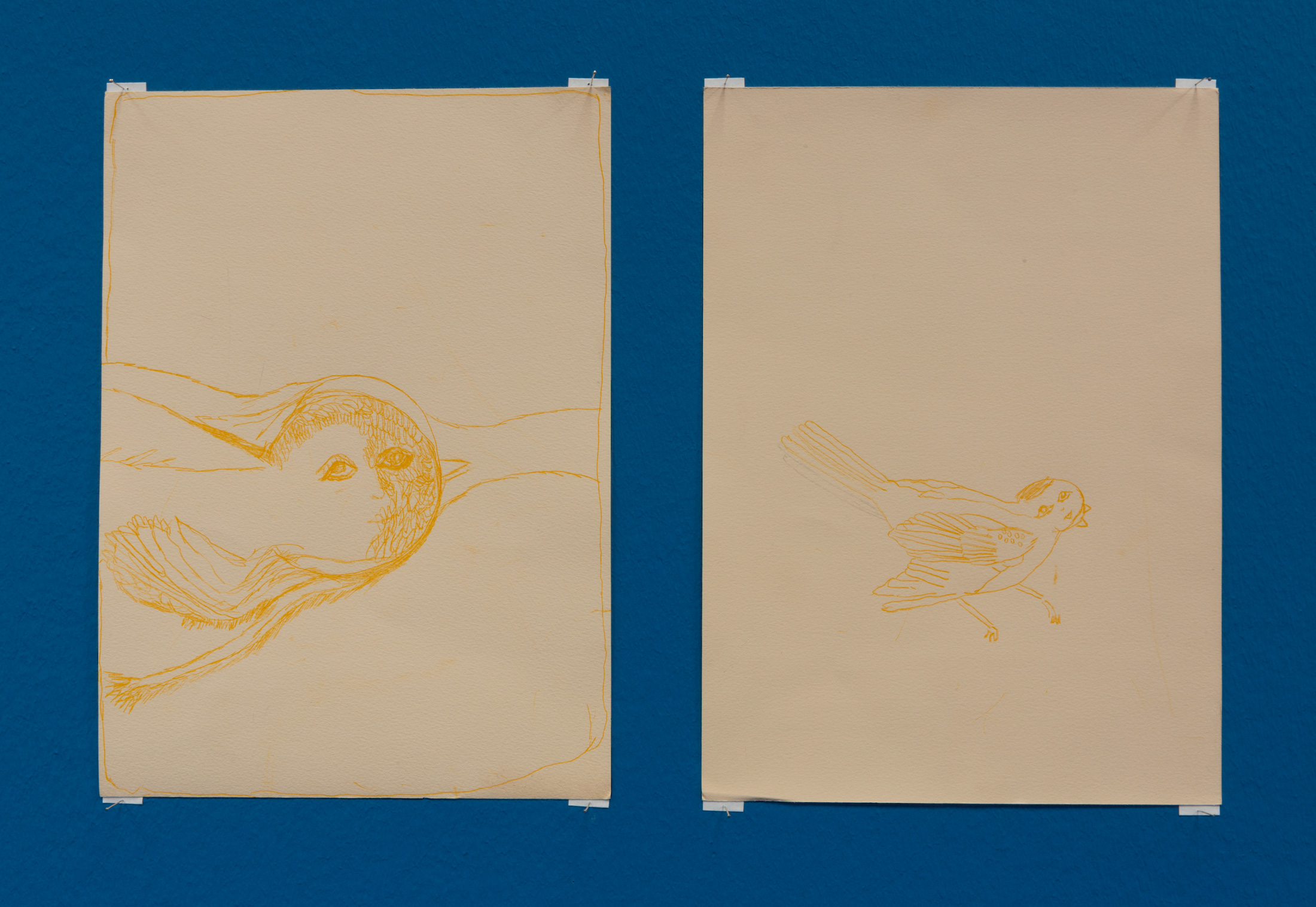

Artists whose works are presented in this exhibition collect and produce not only stories but also objects (drawings, talismans etc.) and rituals connected to them, avoiding the modernist divisions of disciplines. A story is not an immaterial being, it is material because it lives in the (now contaminated) landscape, in a talisman embedded in a similar spiritual world view, in a song and in the act of performing it, in the body of someone that internalized it in their childhood and thinks about it every now and then.

In a way the artists here are like ethnographers; in contrast to traditional ethnographers however they are not treating the magic of the folktales, rituals or the shamans in a manner which objectifies them. They are involved in these practices themselves, believing in them but at the same time retaining some critical distance. They understand the potency for change, the making of communities and counterhegemonic narratives that are at play here. As Kristiina Koskentola emphasized when we spoke: "Subjecting myself to the healing thus incorporating my own body as a subject and at the same time as a medium for this research, making myself both accessible and vulnerable, was a vehicle for making a dialogue. This exchange allowed the shamans for deep and profound access to myself – which then in turn was a way for me to look for an access to the diverse worlds that were mediated through the shamans and their bodies."

Capable of looking at storytelling in the context of the present, the artists in this exhibition bring stories back and adapt, understand and embed them in the daily struggle, releasing their emancipatory potential. The exhibition space becomes much more than a presentation space: it invites one to treat those stories and practices as references for further stories and new rituals.

In Jumana Emil Abboud’s work, Palestinian folktales and talismans give one access to a haunted landscape and a sense of belonging to a cosmology of communities, lives and stories; while Karrabing Film Collective’s work shows us the emancipatory potential for both ancestral ritual and film; Kristiina Koskentola reveals how the shamans of Manchuria and Inner Mongolia practice ritual in the context of a heavily contaminated region where living beings require healing; Black Quantum Futurism use storytelling to bend and break linear time leading to retrieval and change of disenfranchised futures; Melissa E. Logan and Julius Vapiano’s narrative practices reclaim and reinvent urban spaces; Danie Mayer – by means of Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) – reveals the healing potential of biographic narratives anchored in the symbols of flowers, sticks and stones. As for Yasmine Eid Sabbagh her work uses storytelling and the tension between images and texts to bring back four sisters together who had been dispersed from their home country to different corners of the world. The workshops and events in the public program encourage the visitors to use the space as a potential gathering and working space.

Curators: Lara Khaldi and Aneta Rostkowska

Funding and Support

Ministerium für Kultur und Wissenschaft des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen

Kulturamt der Stadt Köln

Hotel Chelsea

Deltax Wirtschafts- und Steuerberatungsgesellschaft mbH

Partner

Internationale Photoszene Köln

Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum - Kulturen der Welt

Transmedialer Raum / Kunsthochschule für Medien Köln

References:

1.Said, Edward (September 1986), Edward Said interviewed by Salman Rushdie. Retrieved July 23, 2020, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAmLNc_4VtE

2. Sotiropoulou, Irene, “‘Why the Sea Is Salty’: Folktales as Sources of Grassroots Economics”, in: The Folklorist in the Marketplace: Conversations at the Crossroads of Vernacular Culture and Economics, Utah State University Press, University Press of Colorado, 2019.

3.Gramsci, Antonio (1985), Selections from Cultural Writings, London, Lawrence & Wishart.

4.Rasheedah Phillips, “Activating Retrocurrences and Reverse Time-Bindings in the Quantum Now(s)”, in: Black Quantum Futurism, On the Edge of the Bush / A Long Walk into the Unknown, exhibition brochure, 2019. The essay is reprinted in the present publication.

Images

1 — Jumana Emil Abboud, “A handless maiden in the mountainous landscape” (I Feel Nothing companion), acrylic, gouache, pastel on paper, 63 x 73 cm, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Lara Khaldi.

2-21 — Tamara Lorenz